Tips compiled from participants in the CHE Place-Based Workshop in Chicago and the Indiana Dunes.

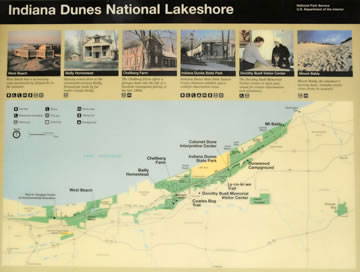

In May 2009, the CHE community embarked on one of its most ambitious Place-Based Workshops in the city of Chicago and environs. Spanning four days, the workshop travelled from Madison to the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, then on to the Chicago neighborhoods of Little Village and West Englewood, the Loop and the Chicago History Museum, and then along the Gold Coast to the north suburbs and beyond.

Before the workshop, participants agreed to use their experiences in Chicago to pull together a series of “tips” for reading the urban landscape. Participants brainstormed and selected a number of themes for organizing their tips. What follows below are the tips they created.

These tips are meant to suggest strategies for approaching the urban environment both as a scholarly traveler and as a curious visitor. While many of these tips were inspired by our experiences in Chicago, they offer ways of observing, asking questions about, and interpreting most urban environments. We hope you enjoy reading them as much we enjoyed putting them together.

Legacy Landscapes

Pay attention to legacy landscapes within the city.

Pay attention to legacy landscapes within the city.

These can point to the historic origins of the city, but also the more recent past. Abandoned structures and remaining foundations help to clue visitors into the recent past of a city. In the case of Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood, residues of past affluence can be seen in vacant lots that once held grocery stores. These remains help to articulate the permeability of neighborhoods and urban poverty, and situate neighborhoods in their temporal context.

The residues of banal and everyday residences and stores help to demonstrate how neighborhoods have changed over time. These remains, themselves representative of past affluence, demonstrate what has been lost in the growth and solidification of poverty in the city.

Contemplate representations – embrace your inner tourist and become a postcard analyst.

Contemplate representations – embrace your inner tourist and become a postcard analyst.

The way a city represents itself to visitors says as much about how it wants to be seen as about how it actually is. Pick up a free tourist map and study it closely. What parts of the city does it include? What points of interest does it highlight? Where does it stop, and what lies beyond its boundaries? Consider who was responsible for producing this map, and whose interests it serves. Think about how this map influences your experience of the city: how it directs you, and how it misleads you. Try to determine what it assumes about a tourist’s interests, desires, and expectations.

Stop at a souvenir shop and examine the postcard racks. Are the places pictured the same as those highlighted on the map? What stories do they tell? Think about what aspects of the city are not captured in these images. Visit a historical museum and consider how the stories it tells about the city’s past relate to the narratives implicit in the tourist map and postcards. Is there consonance and harmony among these stories, or are they dissonant or incoherent?

Go to the musuem.

Go to the musuem.

One must read museum exhibits and other tourist attractions with an open yet critical eye. A lot can be learned about a city’s history by studying museum exhibits. However, one needs to be cautious as these exhibits are a reflection of the donors and other powerful patrons in the city. These forces may downplay or outright dismiss the story of the oppressed and environmental problems in the city. For example, an exhibit at the Chicago History Museum enables children to lie down in an enormous bun and see themselves as a hot dog as they stare up at a mirror on the ceiling.

This hides the dark underside of the meat packing industry that was reported so eloquently in Upton’s Sinclair’s famous 1906 novel The Jungle. The phrase “you are what you eat” could really lead one to make some powerful personal connections with the meat industry in light of the exhibit. However, this type of exhibit in no way leads the observer to be challenged in this way.

Remember the city is a historian.

Remember the city is a historian.

With their concentrations of wealth and population, urban areas are rife with monuments, memorials, and museums charged with preserving the past. But just as the subjectivity of historians seeps into their work, the politics and prejudices of a city shapes the way it presents history. In Chicago’s Lincoln Park, the austere statue of the sixteenth president is flanked by two exerpts from his writings. One, from the Second Inaugural Address, shows him extending mercy to the nearly defeated Confederates.

Another, from an 1862 letter, features him stressing that his commitment to reunion trumps his desire for Emancipation. Reading the monument helps us understand the political and social world of Chicago in 1887, the year the sculpture was unveiled. By then, the majority of white northerners had abandoned their support for the federal civil rights reforms of the Reconstruction era.

With Chicago’s place at the heart of the nation’s industrial awakening and Illinois’s history of barring African Americans from the state in the antebellum period, it is not surprising Chicagoans chose to celebrate Lincoln as the national hero responsible for reuniting the country rather than a sectional figure fighting for the abolition of slavery.

Historic preservation conjures urban ghosts.

Historic preservation conjures urban ghosts.

Urban structures have increasingly become the object of historic preservation efforts. We can consult these preserved buildings, bridges, and other remnants of the urban past almost as we would a medium: they connect us to the ghostly traces of vanished landscapes. Such historic structures help us envision both how a neighborhood may once have looked and how that landscape was lived. The constraints of past building materials dictated floors plans, window sizes, and building heights, significantly determining the shape and feel of daily life, both inside and on the street.

Ornamentation, both in the labor and materials it required and the forms it took, can point to past connections to hinterland quarries and forests, forgotten aesthetic standards, or even now-prohibited labor practices. Evidence of additions, demolitions, and restorations to a given structure – Notre Dame de Paris is a famous example – often document how a site’s uses and meanings have changed over time.

Finally, understanding what it is that a preserved structure commemorates – from its inhabitants to a specific event, from an architectural style to a daily activity – allows us not only to better summon the ghosts of landscapes past, but also to understand contemporary connections to those ghosts. What is it about the site in the present that may have motivated people to preserve elements of its past? What aspects of a site have been selected for commemoration and which ones have been forgotten?

Sensory Geographies

Use more than your eyes.

Use more than your eyes.

Cities are multi-sensorial and demand more than just vision to be properly analyzed. Be conscious of the non-visual cues and encounters that you have in the city. Notice the different sounds and smells found in different places. Inquire into why these sounds and smells differ from place to place, and establish what kind of histories and power dynamics are at work in the production of these different sensorial spaces. Touch is important as well, and the materials of the city are important cues for performing analysis.

Ask what the material tells you about the history of the city. Ask what the current state of the material tells you about the present. Pay attention to material decay and decline. Use material to date the city’s structures. Use material to connect the city and the country, by tracing the flows between construction and extraction.

Finally, immerse yourself in the city in a real way, in the conversations people have, the accents people use, the noises that both excite and startle you, the silences, and the conversations you have with residents. Revel in the cacophony of voices that characterizes the city.

Use your body as an instrument.

Use your body as an instrument.

Entering the urban landscape to read it requires you to leave behind machinery that takes readings of it. Meet this challenge by using the body as an instrument. Treat each of the five senses as a device with which to record and measure the city and the spatial organization of its economy, ecology, and culture. For instance, at one particular intersection, note the persistent hum of the street lamp, the vibration from the underground subway, the stench of the idling garbage truck, and the traffic sign subtitled in Spanish.

At another, register the chirping birds nesting in a string of rooftop gardens and the well-groomed, modern-style buildings they garnish. (Your appetite should remind you to use your sense of taste to your advantage, too!) These sensory experiences-and the geographical differences among them – are initial clues to unraveling the larger mysteries of urban environmental history.

Your nose knows.

Your nose knows.

Paying attention to the “smellscape” provides insight into how a space is used. This can be obvious – for example, the smell of prepared food often indicates a commercial area hosting restaurants and shops. Olfaction can also clue you into the invisible, or at least less noticeable, landscape. Walk over a seemingly benign vent on a city sidewalk or sewer grate and you might be treated the visceral smells from the guts of the city, unseen by those scurrying about on the surface. When you encounter a smell, try to identify it and, perhaps more importantly, ask why you detected this smell here, in this particular place. Knowing what different manufacturing processes smell like allows you to understand what industries are prevalent. It may also be useful to know the direction of the prevailing winds. Winds carry telltale smells (among other things) from nearby factories. Be cognizant of which neighborhoods are downwind from these factories.

Savor the sounds.

Savor the sounds.

A city is rich in contrasting sounds – traffic, street musicians, preachers, secluded gardens, popular parks, even sounding sculptures. Stop for a moment to listen to the musician, the birds, the children playing. How does Chicago’s elevated train sound to a visitor compared to a resident living next to it? How does your sensitivity to this and other sounds change over the course of your stay?

Take a deep breath.

Take a deep breath.

Through the nose. While our noses are constantly feeding us information about urban places, smell can be such a fleeting and under-discussed sense of place that we often forget to put that information to work. Knowing what an urban place smells like – particularly when that knowledge comes at a malodorous price – reveals a lot about life (and not just for humans) in that place and perhaps even how it has changed over time. Bad smells – those produced by garbage dumps, smokestacks, and sewers are great examples – can provide clues to the ways in which a city chooses to dispose of and distribute its waste, often with important social and ecological consequences.

The absence of bad smells – though much harder to register – can be important too. The Chicago River today is an important site for tourist and resident recreation and marks some staggering real estate values. In the nineteenth century, however, the river, so deeply polluted by organic waste, would have made a casual stroll along its banks unthinkable.

Close your eyes and hear the city flow.

Close your eyes and hear the city flow.

Some of the most important information about a city and the areas within it can best be understood by cultivating an awareness of our senses to read a city’s activity and personality without using our eyes. When you close your eyes, what do you hear? Are there people on the streets and sidewalks? Why are they there or absent? What are they doing in this area of town?

Think about the time of day and where people are. The suburban areas may be quiet during the work day, and central business districts may be vacant at night. What does the presence or absence of people tell you about the particular location? Do you hear many cars or trucks? Where are those vehicles going? Is there industry or a highway nearby? How do these parts of the cityscape affect the local residents, land values, safety, mobility, etc.? Do you hear many birds or leaves rustling in the air? Are there many dogs barking? Are children or adults playing nearby? Is there music playing nearby? The sounds of the city can sometimes tell our ears things that our eyes did not notice.

What else do you feel in a landscape?

What else do you feel in a landscape?

Of all we sense in a landscape, one of the most palpable, yet difficult to quantify, is fear. While we might struggle to say exactly how fear maps onto a landscape, take a look around you and ask what people likely fear in this place – is it heavy traffic, noise, pollution, or violence? Would it likely be random violence, or is routine violence? How have residents changed the landscape in response to such fears? Look for locked gates, barred windows, and barking dogs, as well as front door buzzers and security guards in the lobby.

Search for signs of institutional attempts to mitigate fear. Count the number of police cars you see in a given area. Pay attention to neighborhood-watch signs, and those high-tech camera pods that emit an eerie blue light. Consider where such devices are concentrated, and ask whose fear they aim to assuage. Are they likely for anxious residents, or commuters working downtown? Is there a focal point for fear in a given area, or is it more diffuse? Is it a specific street corners or a whole neighborhoods?

Look for signs of how places of fear have changed over time. Have abandoned buildings given way to trendy lofts? Have darkened waterfronts become public greenspace? Keep track of your own sense of fear as you move through a landscape, and think about how it might differ from those who call this landscape home.

Invisibility

Look for what you don’t see at first.

Look for what you don’t see at first.

Bring a map (or guidebook, if possible) and think about what is hidden from view. All landscapes have natural foundations and hidden elements, but you may ask yourself if you can identify/find any elements that may be intentionally hidden. Consider why these elements are hidden and what the influences of this action would have on the local environment and its inhabitants? Who has the authority to cover or conceal part of a landscape and who does not? Why would this be the case?

Make the landscape visible by adjusting your perspective.

Make the landscape visible by adjusting your perspective.

Tall buildings and water taxis attract more tourists than scholars, but reading an urban landscape could change this trend. In a city, what is deemed “invisible” may result simply from an obstructed view. Adjust your frame of reference by getting some relief – topographical relief, that is. Take in the panorama from the top of the Sears Tower or the Space Needle and notice the patterns of land-use that unfold before you. Hop on a boat and see the skyline from sea level, noticing the layered network of highways, bridges, elevated train tracks that urban development produces.

Look for what you don’t see at first.

Look for what you don’t see at first.

Concentrating people and resources into an urban area also concentrates the demand for resources and waste into a relatively small place. Cities depend on thousands upon thousands of acres of rural farmland to produce food for its citizens. Urban dwellers also depend on outside towns to mine and manufacture its cars, precious stones, frying pans, sewer covers, coal, asphalt, steel, and bricks.

The surrounding landscape must also absorb the city’s solid, water, and air waste and pollution. What body of water do the cities sewers drain into? Is the city’s sewer water treated? What happens during floods? You can answer these questions by searching out the city’s sewers or treatment plants and asking people there or just by looking on a topographical map to see how the local watershed basin drains. Where does the city’s waste go? Urban lifestyle’s produce large quantities of (non)biodegradable and (non)recyclable waste. Is there a landfill or recycling plant nearby?

Look at all the tires on the vehicles that pass through the city. Where do those end up once the tread has worn down? What does the city do with hazardous chemical waste from its hospitals and manufacturing industry? By finding out where these wastes end up, you can learn quite a bit about how the residents of the city affect and interact with the surrounding landscape.

Where are the animals?

Where are the animals?

Non-human animals tell stories, too. Look for which types of animals are allowed to be visible and how animals inhabit the landscape. Signs posted behind sturdy iron fences with large, orange letters warning passersby to “Beware of dog” indicate a different utility for domestic animals than signs reading, “Dog contained by invisible fence.” Similarly, observing birds and other urban-based wildlife can provide clues to the unique resources a city might offer fauna, both in terms of food and a “safe” home.

For example, whether a landscape hosts pigeons, Canada geese, or seagulls indicates the presence or absence of particular features within or near an urban landscape. Finally, be mindful of the efforts made to discourage or encourage the use of space by particular species. What species are valued/not valued? Where are they allowed/not allowed? Who decides?

Put on your hard hat and think like a civil engineer.

Put on your hard hat and think like a civil engineer.

Before your boots hit the sidewalk, take the time to learn a bit about urban infrastructure. Think about the unseen machinery of the city, underground, high above, and out-of-the-way: sewers, power lines, tunnels, storm drains, foundations, telephone lines, electrical wires, gas pipelines. Where does the water come from? Where does the sewage go? Where is electricity generated? What parts of the city are serviced by the subway, and what parts are not?

Look at historical and geological maps of the area, and consider the challenges to construction and growth. Is there bedrock to build on, or is the ground unstable? How difficult is it to dig a tunnel here? Are there geographical features that have served as impediments to the city’s commerce or extent? If there is a shoreline, how has it changed over time, and why? Read up on any comprehensive plans that were made for the city. What kinds of visions have people had for this place, and what aspects of them were carried out? How have the city’s many designers coped with the challenges and advantages of this particular spot?

Food

Shop.

Shop.

Stroll through local fish and vegetable markets. A walk through a local market in a city can reveal how productive the local region is for farming or fishing. The diversity and abundance of fruits and vegetables grown on local farms, or lack thereof, could be a reflection of soil and climatic conditions. Fish markets can provide interesting snapshots of the aquatic life in nearby lakes, estuaries, or marine environments and what species are commercially valuable. What you don’t see could be as informative as what you do see, so talk with local merchants and ask questions. People selling at markets are often willing to share stories and experiences and they might offer an intimate glimpse into the dynamics of a local resource.

Eat.

Eat.

One of the most identifying characteristics of a city or an urban neighborhood is its cuisine. Through food, we are transported in time and place – our palettes broadened to experience the flavors of another culture’s crops, spices, and delicacies. Tastes are intertwined with culture, and culinary flair can be taken from the streets of your travels and into your kitchen.

When entering a new urban landscape, it is important to eat locally. Try those strangely wrapped cakes and the extremely hot pepper. Experience the dish that sounds completely unique, and perhaps inedible – as you may be surprised. Not only is traditional food a direct translation of the surrounding landscape, but as a visitor, it is an experience that can relate you to members of your host city – a boundary that can be easily and deliciously crossed.

Drink.

Drink.

Alcohol, like food, is part of the landscape, and to ignore where, how, and by whom it is consumed is to miss something important it can tell you about the place you are exploring. Begin with thinking about the city at a large scale. Where are bars generally located? Are they one after another on a busy commercial corridor, or are they scattered across neighborhoods in a seemingly-random pattern? Zero in on a neighborhood – does that pattern seem so random? Taverns have long sustained the social networks that tie communities together, but that role has changed over time.

With this in mind, think about a bar’s relationship to other commercial activity nearby. Think about the difference between bars in or near a financial district compared to those in an industrial one. What separates these places more than just geography? Next, pick out one establishment for a closer look. From the outside, ask what sort of drinks are likely to be served. Are the signs advertising two-for-one specials on martinis, or on Bud Light? What hours does this place keep? If it opens at 6am, it may well be a “third-shift” bar – if it opens at 4 in the afternoon it likely caters to a 9-5 crowd.

Entering the bar, notice the decor – is it historic photos of the bar over the last century or is off-the-rack nostalgia? Consider how the patrons are drinking – are they young people sharing beer by the pitcher, or are they middle-age people drinking alone? Consider the ratio of men to women. Do the patrons seem to know one another? Would they have likely come on foot ,or have they commuted in for an evening in the city? These are just some of the things to begin with as you explore how a city tipples. Of course, this is difficult research at times, so be sure to bring some friends.

Boundaries

Notice where things change.

Notice where things change.

Consider the purpose, intention, and influence of changes (boundaries) on the landscape. Take a moment to observe a boundary line and the surrounding environment. Ask yourself: Are there any identifiable signs that would help you determine who created the boundary? What is the purpose of intentionally dividing space(s) and creating certain division(s)? What do you believe is (or was) the affect of the imposition of the boundary? Do certain people, plants, or animals benefit from the division? Do any suffer? Has the border been influenced by people, animals, or the nature elements over time, how so, and why?

Once you locate a boundary, ask how permeable it is.

Once you locate a boundary, ask how permeable it is.

Think about the everydayness of the city, the ways in which city streets are navigated by residents and visitors. Think about your everyday routes in your life, and how boundaries structure the walks and paths you choose to take. In the city, think about how these boundaries, always permeable, are nonetheless made concrete through the daily practices of residents and neighbors.

Think about how boundaries are both beneficial and exclusionary, but think about who has the power to cross them. When thinking about environmental justice, think about the beneficial aspects of boundaries, between industry and home or toxicity and need. Then think about how and why these boundaries are collapsed and crossed. Think about who has the ability to transcend and traverse boundaries, and who does not. Think about your own capacity to cross boundaries.

How do boundaries manifest themselves within social interactions?

How do boundaries manifest themselves within social interactions?

Be alert for the social cues that signify “insider status.” What are people wearing? How are they behaving? How are boundaries set, defended, and resisted? Some boundaries might be defended by the state, others might be protected by private entities, still others are established by complex social interactions.

It might be useful is to observe the presence of state-sponsored or privately sanctioned social control. Look for security guards and notice when they or any other law enforcement becomes more alert. Look for the presence of security cameras. Talk with local inhabitants about the less obvious boundary projects such as territories claimed and contested by gangs. Be aware of others’ reactions to your presence and try to understand the reasons for these reactions.

Explore beyond the city’s limits.

Explore beyond the city’s limits.

Urban environments rely heavily upon resources produced outside of the city’s limits. Where does the water, electricity, and food consumed by the urban population come from? Look for examples of how regional, national, and international places support the city and then contemplate what the city returns of value. What does it produce for the outside world? Leave the city and explore the surrounding region, looking for obstacles the city overcame in its development and ways in which the region facilitated development. These relationships have likely changed over time; what aspects have changed most?

Pay attention to your own sense of surprise.

Pay attention to your own sense of surprise.

Dig deeper into your own constructed boundaries between urban and rural environments. When a tick is found, not in the woods or in the dunes, but in the middle of an urban museum, why do we react with surprise and an elevated sense of disgust? Noticing the elements of “nature” that seem particularly out of place among cultural artifacts allows us to question the line between the two. If ticks and other organisms can cross the borders, then so too can our human perspectives and understandings.

Contemporary Change

What used to be here?

What used to be here?

Plants, trees, and other organic matter, it all used to be in the city you are visiting. Rural and urban landscapes may appear to have distinct boundaries, but these are dependent upon time. As a visitor to an urban landscape, consider what might have existed before the neighborhoods, streets and skyscrapers overwhelmed the horizon line.

In order to understand the place you are visiting, it may be helpful to learn about the technological feats and major infrastructure projects that shaped the current urban environment. What elements of the natural environment are still evident? Are there areas of the city that you can visualize the underlying geography? How does the city interact with nature today? Could you imagine the city returned to its natural state in the future?

Read a city’s profile – contemplate the skyline.

Read a city’s profile – contemplate the skyline.

Look at the city from afar. What shape does its skyline take? Some cities have a uniform profile, with buildings all of a similar height, while others contain distinct centers of height and activity. Think about where the tallest buildings are clustered, and what they represent. Where are the residential neighborhoods located in relation to areas of business and manufacturing? Where is the money concentrated? Take note of any prominent geographical features, and consider how they influenced the growth and shape of the city.

Look at the skyline from several vantage points, and note how its shape changes. What features emerge and recede as you change your position? Next, step into the skyline: take in the view from atop one of the taller buildings. Consider what is visible from up here that you cannot see from the street. Are there noticeable patterns to the city’s shape or extent? Note any prominent lines, axes, or areas of activity, and find out what they represent. Compare the views at night with those during the day, and consider how they differ.

Look up.

Look up.

Although it’s easiest in a city to look straight ahead, so as to not run into people or get run over by a car, overcoming this urge, and looking up, can open a new world of questions about the urban landscape. A skyscraper may seem tall when viewed from the top of another building or from across an expanse, but it’s really only when looking up at it from its base that one gets a sense of the enormity of these engineering marvels. Looking up also encourages us to then look down, imagining what lies beneath the high rises and power lines and billboards above us in the city.

Think about who keeps this place clean.

Think about who keeps this place clean.

Keeping urban places clean takes a lot of work and all those monuments and glass towers don’t stay spick and span just by chance. Paying attention to how free of litter and grime places actually are (it’s much easier to notice dirtiness than cleanliness) can tell you a lot about the hidden geographies of labor, capital, and power in a city. Where, how, and for what purpose do resources – both human and financial – get allocated to city cleaning? Knowing who gets to enjoy the benefits of urban cleanliness – whether in the form of a gleaming office spire, immaculate gardens, or spotless tourist attractions – and who works to maintain it reveals a lot about urban landscapes of class privilege.

Also, if you happen to catch a typically immaculate site in the midst of its cleaning regimen, you might try to determine what kinds of grime and litter accumulate there. Do you see museum ticket stubs and transit passes? Food containers? Shopping bags? Leaves or pollen? Compare these “documents” to what you might find in places with fewer resources dedicated to scrubbing and polishing.

Power

Look for landscapes of power in “public” areas.

Look for landscapes of power in “public” areas.

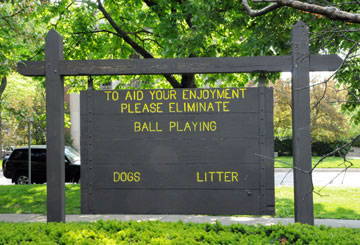

Use a local map to distinguish different bounded areas and see if you are able to identify those divisions from where you are standing. For example, are there signs that categorize, restrict, and/or divide space in a city? The signs are written in what language(s) (i.e. English, Spanish)? Consider who would not be able to read, see, or identify such signs-what are the consequences for these individuals. What are the penalties for violating the regulations? Who decided such regulations were necessary and why?

Analyze the ways that people co-opt spaces for their own uses.

Analyze the ways that people co-opt spaces for their own uses.

In order to understand the differences between intention and reality, notice the ways that people use space other than its designers intended it to be used. What image of a neighborhood might city planners have had when designing a space in a certain way? Why do people choose to flout these designs, and what does this reveal about the desires and demands of a community? Thinking about these disconnects can help us see the social fault lines present in a neighborhood and the need for community-based planning.

Space available.

Space available.

A central question to ask in any landscape is, who owns this place? The density of urban areas and the multiple uses of space makes finding answers difficult – but before giving up at the thought of digging out tax maps and probate records, consider the basic evidence on the street. Begin with “For Rent” signs. How many of them are there? Where are they clustered? What are they renting – storage space, office space, or condo space? Consider what these different uses of space tell you about an area’s cultural geography? Take notice of the names and numbers on the sign. Does real estate appear to be locally-owned, or managed by a property company?

Another easy way to answer these questions is to grab an apartment circular and consider the evidence you find there. Are the apartments in brand new buildings, or are they carved out of old manufacturing spaces? Think about the relative costs of the various forms of housing you see. How much does it cost to own a piece of this urban space? How has that cost changed over time? Who used to own this place? By this point you might ready for those old tax maps, but now you’ll know better how they shape the landscape around you.

Consider lawns as agricultural productions.

Consider lawns as agricultural productions.

While we often contrast urban landscapes against their rural counterparts, city and country share more attributes than we might at first expect. Even if urban gardens are few and far between, cities are full of ongoing efforts to wrest control over vegetation.

Ask the same sorts of questions of landscaping as you would of farming: How does land use change as land ownership changes? How do the gardens and lawns differ among commercial property, public lands, and individual homes? What types of energy sources are landscapers depending on? What new biota and synthetic concoctions are being introduced to these ecosystems? Who is doing the labor? How does landscapers’ work place them in an economic relationship with others in the city and in a physiological relationship with urban green space?

Look next door.

Look next door.

Learn about residential neighborhoods next to heavy industries such as power plants and landfills. Several factors (economic, social, historical, political, etc.) play a role in determining who lives in the areas of a city that are deemed to have higher public health risks. Are there ethnic groups whose settlement predated the arrival of a heavy industry business to a site and who remain there in part because of strong social support networks? Are property taxes lower there? Were there restrictive real estate codes that prevented people from settling in other locations?

In a practice that was later declared illegal by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948 (Shelley v. Kraemer), for example, cities across the northern United States “redlined” certain locations; African Americans resettling to those cities in search of jobs between the two World Wars were prevented from moving to numerous neighborhoods by restrictive covenants among existing residents. Many racial and ethic groups continue to fight against this legacy and other forms of discrimination that prevent full access to city resources such as health care clinics and public transportation.

Keep your eyes peeled for class markers.

Keep your eyes peeled for class markers.

You may instinctively see a residence and begin making conjectures about property values and the social position of its inhabitants. While always an inexact science (and sometimes fraught with prejudices), looking for trends can help you navigate the geography of a city’s social classes. The architecture of a quaint suburban downtown might not immediately betray its large number of upper-class patrons, but a row of expensive cars will. Likewise, a check-cashing outlet might appear in lots of corners of a city, but a concentration of several within a few blocks signals a neighborhood with a large working-class population – one potentially underserved by banks and credit institutions. As you move through town, try making a mental map of foreclosures, parks, or grocery stores and overlaying it on the city’s transportation networks, topography, or racial and ethnic geography.

Understand neighborhood power dynamics.

Understand neighborhood power dynamics.

If mayors are the generals of urban politics, aldermen (and alderwomen) constitute the troops on the frontlines. These elected officials are stationed in every corner of city and are responsible for commanding their territories and the people who inhabit them. In many cases, neighborhood power relationships play out like warfare: battles for green spaces, for instance, are won or lost — and those who fought in vain may retreat with enough wounds that make future interactions with the victors combative.

Aldermen are key informants to understanding encounters among citizens and between communities. Getting to know them unlocks some of the facets of power in an urban setting, in both contemporary and historical contexts.

Flows

Follow time in space.

Follow time in space.

In the mid-twentieth century, ecologists who lived in Chicago took the train out to the Indiana Dunes to study plant succession. The rapidly-changing dunes provided a great laboratory because there ecologists could plausibly map space onto time, reading the changes in plant life as they moved inland across the dunes as changes over time. While both stories of industrial progress and environmentalist narratives of decline could cast the steel mills and slag pond in the background of this photo as another kind of “succession,” to be advocated or resisted, the smokestacks should in fact caution us against any simple mapping of space as time.

Events cultural and natural — not just industrial development — leave their traces, making each place into the jumble of artifacts that it is. We have to bring geology, ecology, and history together to understand how the plants, sand, buildings, and waste here testify to distinct historical trajectories and discontinuous patches of the past.

Follow the water.

Follow the water.

Walk around in the rain and watch the flow of water. Rain falling in an urban environment will often fall upon streets, sidewalks, parking lots, and other impervious surfaces that prevent the infiltration of water directly into the ground.

Curbs and gutters direct the flow of stormwater below ground through drains and networks of pipes that can transport it great distances before it is treated or released into aquatic ecosystems. Watch the flow of water in a storm, imagine where it flowed historically, and contemplate the effects of these changes on the local and regional environment over time.

Follow the people.

Follow the people.

See how people get from here to there, and do it yourself. Transportation affects peoples use, views, and experience of landscapes. As transportation changed from carriages to street cars to personal cars, people modified not only how they moved through urban areas but also where they lived, worked, and spent leisure time.

Follow energy to its source.

Follow energy to its source.

Physical geography is one of the most influential factors responsible for how a center of economic activity develop. Some cities were aptly placed near rivers, oceans, on lakes, and in natural inland ports. Other more modern cities have constructed near major transportation corridors — both contributing to and benefitting from road and rail projects. When visiting a place, it is important to consider the types of infrastructure used that makes the city work.

For example, you might consider the unique characteristics of a region’s power supply. Is it shipped from distant wind farms or coal plants, or is the area supplied with power produced from a local hydraulic dam? Is the intensity of infrastructure evidence of an area which has been or remains a large manufacturing center? You may learn about the history and future of an urban landscape from taking into consideration the many infrastructure choices made to mobilize and electrify a region.

Themes

Themes